The Archiv der Avantgarden — Egidio Marzona (ADA), Dresden

April 11 – August 10, 2025

Arindam Sen. December, 2025

The Modern Times exhibition at ADA in Dresden is a unique archival deep dive into the transatlantic encounters of the Golden Twenties when an avant-garde took shape as a result of a symbiotic exchange between Americanism – skyscrapers, jazz, Hollywood and Chaplin, Taylorism and Fordism – and the various European isms namely Italian Futurism, Dadaism, Soviet Constructivism, French Purism, and Czech Poetism. Printed matter such as books, catalogs, posters, photographs, and magazines were crucial for the transmission of ideas across the Atlantic, as were films, the two core emphases of the exhibition.

Entering the exhibition space, the first film that catches one’s attention is Robert Florey’s Skyscraper Symphony (1929), projected on a large-screen with a black curtain in the background. Florey, focussing entirely on the high-rise buildings of postwar Manhattan using low angle shots, upward and downward tilts, pans, and dissolves, conveys a disorienting urban experience where the spectator feels not only dazzled but also confused by the lack of their own ability to organize the filmic space on perspectival lines. New York’s skyscrapers – a direct result of increasing land worth and urban congestion – became one of the viral images of American modernity and the emergence of a new industrial society. It thrilled Le Corbusier and some years later, Piet Mondrian. It found its way to various Futurist publications, some present in the exhibition such as Ivanhoe Gambini’s design for Arnaldo Fraccaroli’s New York, Ciclone di Genti (Milan, 1929), El Lissitzky’s cover for Richard J. Neutra’s Amerika (Vienna, 1930), Mario Castagneri’s photomontage for a leaflet of Fortunato Depero’s unpublished book Film Visutto that he was preparing in 1930, and Charles Sheeler’s painting Skyscrapers in New York published on the pages of Futurist Aristocracy (1923, ed. Nanni Leone Castelli). Not everyone was jubilant in their depiction of the iconic symbol of American capitalism, the cover of Czech poet Jaroslav Seifert’s book Samá láska (Prague, 1923) was illustrated by Otakar Mrkvička depicting a red star over Bankers Trust Company Building in New York, while the cover design by Hugo Gellert in 1928 for leftist American magazine New Masses shows skyscrapers rising above branched out trees signalling its arrogant disregard for nature.

Quivering skyscrapers, geometrical designs characteristic of the machine age, and filmstrips denoting Hollywood complemented by newsreel-style street shots create the visual world where a certain Mr. Jones fails to realize his Hollywood dream in Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapich’s expressionist short film The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra (1928), also presented in the exhibition. A casting director assigns Jones the number 9413, his quest for work never materializes, as he constantly encounters a banner that reads “no casting today” while other actors taste success. Mounting bills and numerous phone calls to no avail lead him to despair and finally death and it’s only in heaven that he is able to rid himself of his identification number. Life and Death presents the city as a dream machine where its verticality is egging on everyone to keep rising. The word “Success” appears at various times, always followed by a symbolically charged cut – to someone hammering the alphabets on a typewriter, an upward tilt along a skyscraper, and this one time, a staircase that 9413 is unable to ascend with the ease he is expected to.

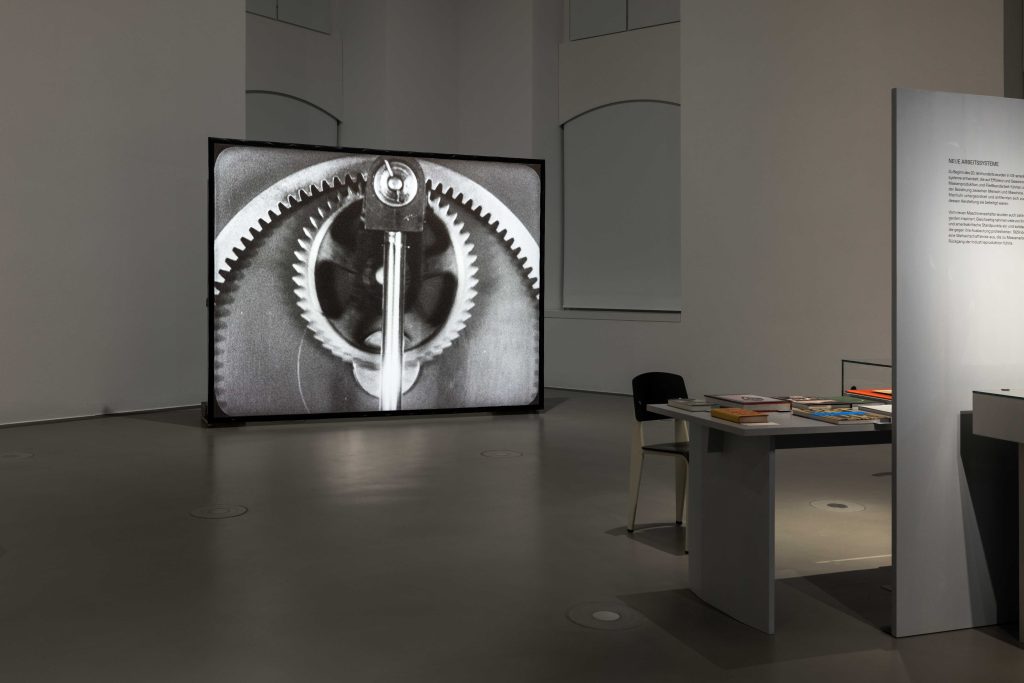

The circulation of Hollywood films in post first world war Europe ushered in the possibility of a new world, its exuberance served as an alternative for the battered old continent. Simultaneously, the machine age aesthetic of America which owed its prominence to models of Capitalist production such as Taylorism and Fordism was beginning to co-mingle with avant-garde movements in Europe. In the exhibition we also see Ralph Steiner’s Mechanical Principles (1930), a dance of machine parts such as pistons, shafts, pulleys, gears, screws, and other widgets leading to a kinetic poem of grace and rhythm. Not too far away, displayed are the issues of the magazine New Masses which frequently published Louis Lozowick’s Machine Ornaments – abstract geometric designs of machine parts in black and white – in the mid to late 1920s. The exhibition’s curator Przemysław Strożek in his catalogue essay marks out Lozowick’s pursuit to combine the tenets of American Capitalism with experiments of Soviet Constructivism as a linchpin for the exhibition aside from the more obvious figure of Charlie Chaplin. Lozowick’s texts on art and industry were published in some of the key publications of the time that are the highlights of this exhibition: the catalogs of Société Anonyme led by Katherine S. Dreier, Jane Heap’s The Little Review, and the magazine Broom. Lozowick met Ivan Goll and Fernand Léger in 1920 in Paris, the same year the latter two collaborated on the famous film-poem book Die Chapliniade published in Dresden.

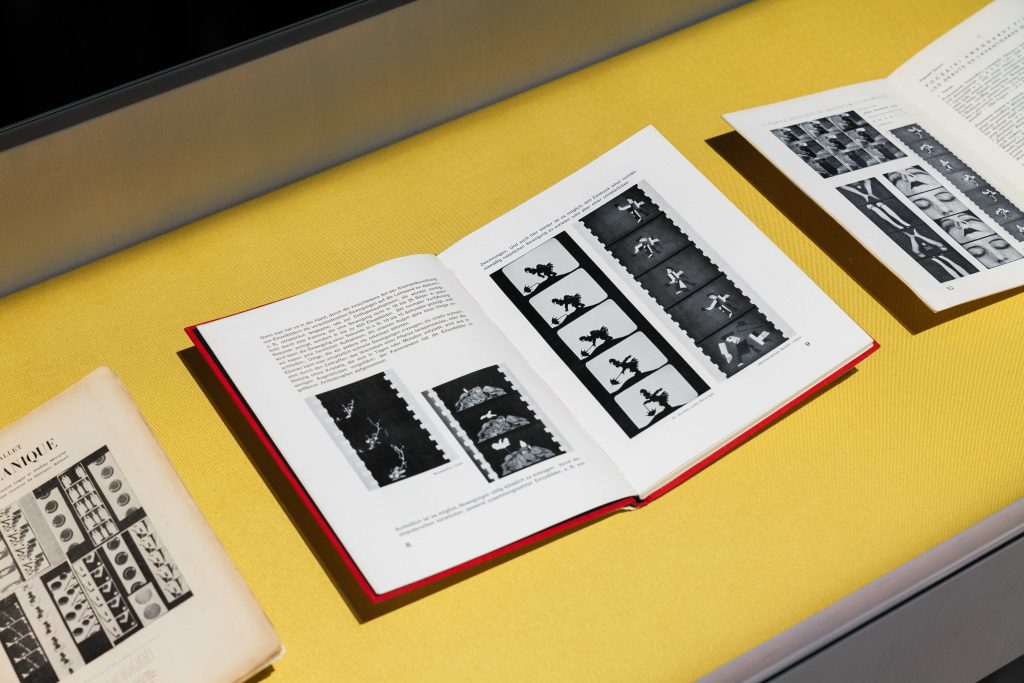

The most obvious film to which the exhibition alludes to or rather, conceptually draws upon, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936), is not among the films included in it, not even an excerpted version. It is perhaps an acknowledgement of the film’s popularity that allows it to be referenced without being shown. It could also be that the exhibition intends to portray the roaring twenties through film and literature from the decade rather than reaching out to its vast legacy. Either way it seems like a wise choice. In its absence, Ballet Mécanique (1924) by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy is the most iconic film in the exhibition. Chaplin, whom Léger saw as a cinematographic invention, appears at the beginning of the film as Charlot Cubiste. Charlot – who Léger first saw on the screens of a Parisian cinema while on leave from his war duties in 1916 – was an intoxicating persona on European screens in the 1910s (except in Germany where Chaplin’s films were not shown). Among other fascinating documents on the film such as Stefan Themerson’s Film Artystyczny (Warsaw, 1937) and Hans Richter’s Filmgegner von Heute (Berlin, 1929), the exhibition displays the pages of L’Esprit Nouveau from 1925. Here Léger presented a two page textual and visual account of his pursuit of pure form in the film. Charlot is conspicuously absent, as Jennifer J. Wild notes in her catalog essay, for Léger, Chaplin’s Hollywood stardom got in the way of his purist aims.

The exhibition, featuring nearly 170 objects, activates a layered narrative on artistic inclinations, industrial advancement, and unrealized utopias of the interwar years, some of which remain elusive even on multiple visits. 100 years on, the relationship between art and technology has transformed radically. An affirmative view of industrial modernization, particularly its American counterpart, ushering in a newer and just society might have always had its detractors within the cultural left, but nonetheless, advanced art in the roaring twenties was shaped by an openness towards the machine age that challenged artists to scale new aesthetic frontiers. The 1960s came with its own set of paradoxes, on the one hand, a sense of collective achievement in the Apollo moon landing, and on the other, a synergic solidarity with the resistance against American imperialism in Vietnam. What we understand as Political Modernism from this era is an articulation of such paradoxes and frictions. Today, whatever new formal possibilities generative AI, space tourism, sophisticated surveillance technology, or neuromorphic computing might have to offer, it’s hard to imagine deep speculation not overriding even a critical form of their absorption within radical artistic practices. In other words, the great promise of a bonhomie between art and industry seems to have been exhausted at this stage in late Capitalism. And so perhaps, the idea of an avant-garde itself, that can now only find relevance as a historical category and not so much as something that constantly negotiates its place in the present. As the exhibition attests to, it’s still something worth reckoning.